Introduction

In August 2023, Google published research they did on AI-powered fuzzing. They showed they could automatically improve fuzzing code coverage of C/C++ projects already enrolled in OSS-Fuzz thanks to AI. They found that for 14/31 (or 45%) of the projects on which this research was conducted, generated fuzz targets successfully built.

This research inspired us, and we thought we could expand on this work and bring something new to the table. Previous research started with projects that already did fuzzing. Indeed, all projects enrolled in OSS-Fuzz have at least one existing working fuzz target, and this is what was used in the above research to build prompts. We wanted to go a step further and be able to start fuzzing projects completely from scratch when no working fuzz target examples for the project under test already exist.

To maximize success, we decided to focus on projects written in Rust. Not just because we love Rust. It’s because of the high consistency in project structure usually observed in projects written in that language. Indeed, most projects use Cargo as their build system, and that minimizes fragmentation in the Rust ecosystem. There are many assumptions that can be made about a Rust code base because its easy to know how to build it, where to find unit tests, examples, and its dependencies.

With that into consideration, it was time to build something that would be capable of automatically fuzzing Rust projects from scratch, even if these projects didn’t do any fuzzing at all.

Our contributions

We built Fuzzomatic, an automated fuzz target generator and bug finder for Rust projects, written in Python. Fuzzomatic is capable of generating fuzz targets that successfully build for a Rust project, completely from scratch. Sometimes the target will build but it won’t do anything useful. We detect these cases by evaluating whether the code coverage increases significantly when running the fuzzer. In successful cases, the target is going to do something useful, such as calling a function of the project under test with random input. It will also sometimes automatically find panics in the code base under test. The tool reports whether the generated target successfully builds and whether a bug was found.

How does it work?

Fuzzomatic relies on libFuzzer and cargo-fuzz as a backend. It also uses a variety of approaches that combine AI and deterministic techniques to achieve its goal.

We used the OpenAI API to generate and fix fuzz targets in our approaches. We mostly used the gpt-3.5-turbo and gpt-3.5-turbo-16k models. The latter is used as a fallback when our prompts are longer than what the former supports.

Fuzz targets and coverage-guided fuzzing

The output of the first step is a source code file: a fuzz target. A libFuzzer fuzz target in Rust looks like this:

#![no_main]

extern crate libfuzzer_sys;

use mylib_under_test::MyModule;

use libfuzzer_sys::fuzz_target;

fuzz_target!(|data: &[u8]| {

// fuzzed code goes here

if let Ok(input) = std::str::from_utf8(data) {

MyModule::target_function(input);

}

});

This fuzz target needs to be compiled into an executable. As you can see, this program depends on libFuzzer and also depends on the library under test, here “mylib_under_test”. The “fuzz_target!” macro makes it easy for us to just write what needs to be called, provided that we receive a byte slice, the “data” variable in the above example. Here we convert these bytes to a UTF-8 string and call our target function and pass that string as an argument. LibFuzzer takes care of calling our fuzz target repeatedly with random bytes. It measures the code coverage to assess whether the random input helps cover more code. We say it’s coverage-guided fuzzing.

Making fuzz targets useful

Once we have generated a fuzz target, we try to compile it. If it compiles successfully, that’s great, and we run the compiled executable for a maximum of 10 seconds. We capture the standard output (stdout) of the fuzz target and evaluate whether code coverage changes significantly. If that’s the case, we can be quite confident that the fuzz target is doing something useful. We say that the target is “useful” in that case. Indeed, if we generate an empty fuzz target or one that calls a function with a constant or that doesn’t use the random input at all, the code coverage shouldn’t vary too much. This may not be 100% accurate, but we found that it’s a good enough metric.

We also detect when the fuzzer crashes. When that happens, we have a look at the stack trace in the standard output and see whether the crash happened in the fuzz target itself or in the code base under test. If it’s in the code base under test, then we likely found a bug.

Fixing compilation errors

If the fuzz target does not build, we feed the compilation errors and the fuzz target to the LLM and ask it to fix the code without modifying its behavior. Applying this technique multiple times usually results in a fuzz target that successfully builds. If not, we move on to the next approach.

To minimize the LLM costs, we turn off compilation warnings and only get errors because warnings do not really help fix the errors and are quite verbose. In addition, the longer the compilation error, the more tokens they would turn into, and the more we would have to pay. Indeed, OpenAI charges per token processed.

Fixing dependency issues

At first, the most common compilation error was because of incorrect or missing dependencies. Indeed, the LLM may generate a code snippet that imports a module from the library under test, but this import statement may be incorrect. Alternatively, some import statements may be missing. To minimize dependency issues and reduce the amount of LLM calls, we do two things:

- Add all dependencies of the code base under test to the fuzz project’s dependencies

- Detect missing dependencies in compiler output and automatically add crates to the fuzz project’s Cargo dependencies with “cargo add”

Even with this, we still had compilation errors due to incorrect imports. We significantly reduced that kind of error rate by adding a new approach: the “functions” approach. But first, let’s see what those approaches are.

Approaches

The approaches we attempt include:

- Using the README file, as it may contain usage examples of the library under test

- Using the source files in the “examples” directory

- Looking for unit tests as examples

- Using benchmarks in the “benches” directory as examples

- Identifying all public functions and their arguments and calling some of those functions

The approaches are attempted one by one, until one works and gives us a useful fuzz target.

README approach

This approach is pretty simple. If there’s a README file in the code base, we read its contents and use it to build a prompt for the LLM. In that prompt, we ask the LLM to generate a fuzz target, given the README file.

This approach clearly doesn’t work if the README file only contains installation instructions, for example. If it contains example code snippets that show how to use the library under test, then it is likely to work.

We’ve seen projects where the README contains code snippets that contain errors. For example, one project had not updated the README file in a long time, and it went out of sync with the actual code base. Therefore, the code snippet in the README file would not build. In such cases, this approach may not work either.

Examples and benchmarks approaches

The examples approach is similar to the README approach. The only difference is that we use the Rust files in the “examples” directory instead of the README file. The benchmark approach is essentially the same thing, except that it uses the Rust files in the “benches” directory.

Unit tests approach

We use semgrep to identify pieces of code that have a “#[test]” attribute and feed them to the LLM. We also try to capture the imports and potential side functions that may be defined next to a unit test. We arbitrarily limit this approach to try at most 3 unit tests and not all of them to keep the execution time to reasonable levels. The unit tests that are the shortest are used first to minimize AI costs.

Functions approach

We first obtain a list of all the public functions in the code base under test. This is achieved by running “cargo rustdoc” and asking it to output to JSON format. This is an unstable feature and requires passing some arguments to “rustdoc” to make it work. However, this is a really powerful feature because it gives information straight from the compiler, which would have been much more difficult to accurately obtain with static analysis. We can then parse the generated JSON file and extract all the public functions and their arguments, including their type. In addition to that, we also get the path to the identified function. For example, if we have a library named “mylib” that contains a module named “mymod”, which contains a function “func”, its path would be “mylib::mymod::func”. Rustdoc uses the compiler’s internal representation of the program to obtain accurate information about where each function is located and this is always correct. With this information, we can kiss the import errors we previously had goodbye.

Getting the import path right is one thing, but that won’t produce a useful fuzz target on its own. To get closer to that, we give a score to each function based on the type of arguments it takes, the number of arguments it takes, and the name of the function itself. For example, a function that contains “parse” in its name may be a good target to fuzz. Also, a function that only takes a byte array as input looks like something that would be easy to call automatically. We select the top 8 functions based on their score, and for each of these functions, we try generating a fuzz target that calls that function using a template. If the build fails, we fall back to asking the LLM to fix it.

Another challenge is to convert the random input bytes into the appropriate type the function takes as an argument. This can become even more complicated when a function has multiple arguments of different types.

In that case, we leverage the Arbitrary crate to split those bytes and automatically convert them into the required types the function takes as arguments. This way, we support any combination of arguments of a supported type.

This approach works surprisingly well and is able to produce useful targets most of the time, as long as there is at least one public function with arguments of a supported type.

Results

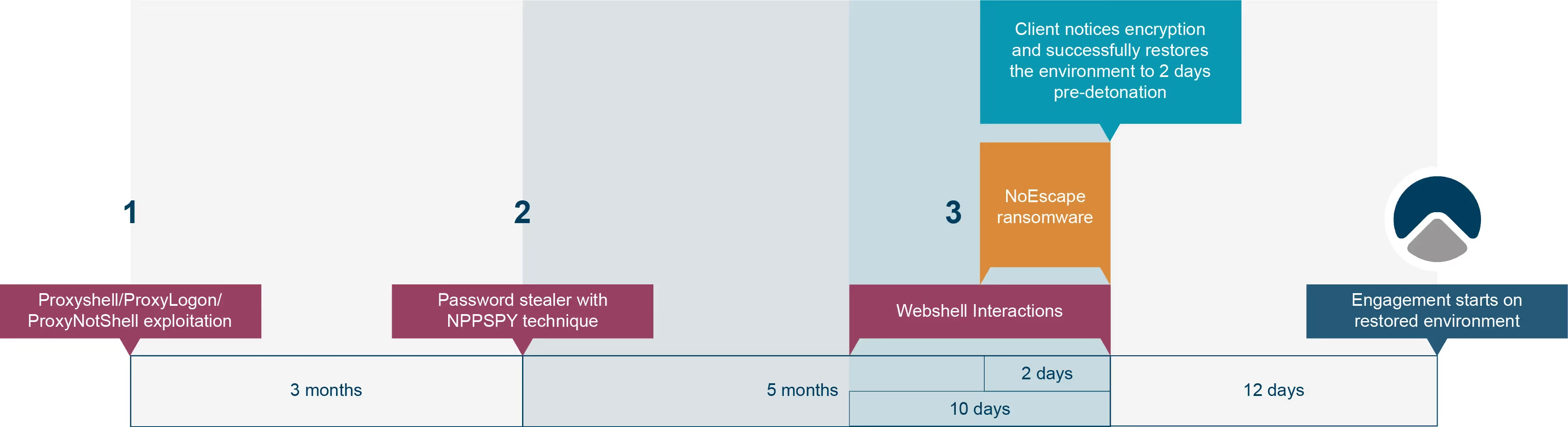

We ran Fuzzomatic on the top 50 most starred GitHub projects written in Rust that matched the search terms “parser library.” We detected six projects that were already doing some sort of fuzzing and 1 project that was not a Cargo project, so we skipped those. There were also 6 projects that did not build, so these were discarded as well. This left us with 37 projects that were candidates for being processed.

Out of those 37 projects, no approach worked for 2 projects. At least one fuzz target that was compiled successfully was generated for each of the other 35 projects. That’s a 95% success rate.

For only one project, no useful fuzz target was generated. But for 34/37 projects, at least one useful fuzz target was generated. That’s a 92% success rate. We also found at least one bug in 14 projects or 38% of those projects.

The whole process took less than 12 hours. On average, it took 18 minutes to process a project where at least one successful fuzz target was generated. But we’ve seen some take just over two minutes and others take as long as 57 minutes. These numbers cover the whole process, including compilation time.

Considering projects where bugs were found, the “functions” approach was the most successful: 77% of fuzz targets that found a bug were generated using that approach. Next, the README approach worked for 12% of those targets. The examples approach worked for 8% of targets thanks to which bugs were found. Finally, the benchmarks approach worked for 4% of those targets.

When we look at useful generated fuzz targets, the “functions” approach is still the most efficient with 62% of targets generated with that approach. It is followed by the examples approach (13% of useful targets), the unit tests approach (12%), the README approach (10%) and finally the benchmarks approach with 1% of useful targets.

The OpenAI API costs summed up to 2.90 USD, which is quite cheap considering this ran on 50 projects. Usually, it only costs a few cents to run Fuzzomatic on a project.

What kind of bugs did we find? Those 14 bugs were composed of:

- 1 byte slice to UTF-8 string conversion failure

- 2 calls to panic!()

- 2 calls to assert!()

- 1 creation of a too large vector (vec![0, 12080808863958804234])

- 4 slice/array indexing errors

- 4 integer overflows during multiplication, left shift and subtraction

Most of the bugs we found were making the software under test crash. But, under some different conditions, this may not be true, depending on how the project is built. Indeed, integer overflows are not checked by default when a Rust program is compiled in release mode. In that scenario, the program would not crash, and may silently produce unexpected behavior that may cause a vulnerability.

Lessons learned

Fuzzing code bases completely from scratch has requirements

We’ve shown that this is possible and worked in most cases, but that’s clearly not the case for every code base out there. Here are some requirements:

- The project needs to be in a buildable state

- All external (non-Rust) dependencies need to be installed

- The project must have at least something that makes one of the approaches succeed:

- A README file with example code snippets that actually work!

- Unit tests or benchmarks

- Public functions that were designed to be tested

If a single top-level item in that list is not fulfilled, then this will likely not succeed.

Fuzzomatic doesn’t replace manual fuzzing

The results we obtained show that for parser libraries, Fuzzomatic was pretty effective. This strategy can find low-hanging fruit automatically when the right conditions are present, but it won’t be as effective as manually writing a fuzz target with in-depth knowledge of the target code base. However, when it does succeed in finding a bug, it usually does so much faster than it would have taken to get familiar with the code base and manually write a fuzz target for it.

Unsuccessful attempts still provide value

Even if the generated fuzz target does not build, it may still be used as a starting point for manually writing a good fuzz target. Maybe automatically producing a fuzz target that builds did not work, but the fix may be obvious to a person reviewing the generated code. Being able to start from that and not entirely from scratch may save developers a lot of time. Automatically generating a draft fuzz target, which potentially has an import issue but that already calls an interesting function, adds some value, and saves time.

Non-exploitable bugs are still useful

Sometimes, bugs are found, but they may not be exploitable. Even if the bugs found are not directly exploitable, that result in itself provides useful information. Indeed, if some bugs can be found automatically in a code base, it is likely that there is more to be found in that code base, and it opens the path for a more in-depth review of that code base. Also, the bug may not cause any security issues at all, but it’s still nice to fix it anyway.

Using Fuzzomatic

Fuzzomatic can be used as a defensive measure to protect one’s own open source project. It’s very easy to run. There are only a few requirements that must be respected.

Requirements

Fuzzomatic focuses on projects written in Rust, so it is required that the target code base is written in that language.

The project must build successfully when running “cargo build”. A project that does not build cannot be fuzzed. This is probably the most important requirement. There are tons of GitHub projects that simply do not build out there.

Functions in your code base should be designed to be tested. One common pitfall we’ve seen in many libraries is exposing a function that takes a path to a file as an argument but not exposing any function that takes the contents of a file directly, for example, as a string or as a byte array. This is an anti-pattern that needs to stop. When designing a library, make sure that your functions are easy to test. This way, automated fuzzing will be much more effective.

Finally, any external non-Rust dependency should already be installed on the system where Fuzzomatic will run. Fuzzomatic currently doesn’t support installing non-Rust dependencies and won’t do it automatically.

Warning: Security considerations

To achieve its goal, Fuzzomatic may run untrusted code, so make sure to always run it in an isolated environment. Indeed, it will build untrusted projects. Building untrusted code is a security concern because we never know what’s inside the build script.

Fuzzomatic will also run arbitrary code output by an LLM. Imagine what would happen if, for example, the README file of a project contained malicious instructions, fuzzomatic built a prompt with it and called the LLM. The LLM may respond with a malicious code snippet that would be built and run.

Also, if Fuzzomatic is run against an unknown code base, there is no way to know what the functions that will be called will do. An unknown function may very well delete files or perform other destructive operations.

Therefore, always make sure to run Fuzzomatic in an isolated environment.

Fuzzomatic as a continuous defensive measure

Fuzzomatic can run in your CI/CD pipeline. It can also be used once to bootstrap fuzzing for projects that don’t do any fuzzing at all. It saves time and can identify which functions of your codebase should be called and will write the fuzz target for you. In some cases, it will even find runtime bugs in your code, such as panics or overflows.

Fuzzomatic as an offensive tool

Fuzzomatic can also be set to run on a large number of projects, hoping to find bugs automatically through fuzzing. We’ve shown that this approach works and found 14 bugs out of 50 parser libraries.

Keeping the source code private

If sending parts of the source code to OpenAI is a problem, fear not. There are plenty of alternatives. We’ve seen that the Mistral 7B instruct model also works, and it can be hosted locally. With tools like LM Studio, a local inference server can be set up in just a few clicks. Then, since that server is API compatible with OpenAI, it’s as easy as setting the OPENAI_API_BASE environment variable to http://localhost:1234/v1, and then Fuzzomatic can run using the model of your choice on your own server. Your code remains private.

Further research

There are other approaches we didn’t try or implement. One example is to extract code snippets that are inside docstrings. Many projects include code examples inside multi-line comments that document modules or functions. These examples could be fed to the LLM to generate a fuzz target.

Even though the Rust ecosystem guarantees some structure in most projects, that structure can quickly become complex. Fuzzomatic does support quite a bit of Cargo’s features and is capable of handling Cargo workspace projects with multiple workspace member crates for example. However, we haven’t tried to support all Cargo features, such as [build-dependencies], [patch.crates-io] or target-specific dependencies, to name a few, and there are still projects where Fuzzomatic may fail because of this.

External non-Rust dependencies are a problem and are one of the reasons why some projects would not build by default. Automatically installing these would help with automated fuzzing from scratch.

The default branch of a repository may not always be in a building state. Another strategy may be to check out the latest tag or release and target that instead of the latest commit.

Optimizations regarding costs and benefits when using commercial LLMs may be implemented. For example, retrying with a larger model (such as GPT-4) when all other approaches fail. This way, we first try a cost-effective approach, and then use a more expensive one as a last resort. This could be an option to avoid exceeding budgets quickly.

Sometimes, the LLM enters a code fix loop where it suggests the same fix over and over again which doesn’t help in making the fuzz target compile at all. Detecting these cases and failing fast would reduce costs and runtime.

Unit tests sometimes contain test vectors that could be used to automatically generate a seed corpus. So far, we haven’t used a seed corpus at all. Doing so may significantly speed up the discovery of bugs while the fuzzer runs.

Some bugs may not be found because the fuzzer didn’t run for long enough. Currently, Fuzzomatic runs fuzzers for 10 seconds only. An improvement may be to do a 2nd pass on useful fuzz targets and re-run them for a longer time, hoping to find more bugs.

Adding support for more function argument types would help improve Fuzzomatic’s functions approach effectiveness. Support for functions using generic types and more primitive types, for example. Also, being able to generate fuzz targets that instantiate structs and call struct methods would help cover more ground of a code base.

To help as many developers as possible improve the security of their code, it would be even better to support other programming languages, such as C/C++, Java, Python and Go.

Conclusions

We’ve shown that it is possible to generate fuzz targets that successfully build completely from scratch and that do something useful for Cargo-based projects. We’ve even found crashes in code bases completely automatically with this technique.

For security reasons, make sure to always run Fuzzomatic in an isolated environment.

Fuzzomatic is open source and available on Github here. We hope that open-sourcing this tool will help projects find bugs in their own code and improve their overall security posture. We also hope to contribute to automated fuzzing research by sharing what we learned along the way while performing this experiment.

References

.avif)

.png)

![[0,2^{\log_2(q)+256}]](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67711be5796275bf61eaabfc/685923a3be396e651b30e954_latex.png)